In recent weeks, several states have raced to redraw their congressional maps, with parties looking to preserve or improve their chances ahead of 2026. Last Tuesday, California voters passed Prop 50, which will allow Democrats to redraw congressional districts to their own advantage, following similar efforts by Republicans in Texas, Missouri, Ohio, Utah and North Carolina.

But sometimes, when it comes to gerrymandering, politicians press their advantages too far. Political scientists have a term for parties spreading their vote perilously thin through redistricting: dummymanders. The idea is that, by spreading a party’s voters more thinly across a greater number of districts in order to pick up more seats, a new map will turn strongholds into potential areas of danger. Instead of having five districts where the party can generally count on 60 percent support, say, they’ll create seven districts where their likely share is more like 53 percent — leaving more of them at risk during a wave election.

Some observers had already started to wonder if Republicans had been guilty of dummymanders in their newly redrawn 2026 maps, but Tuesday’s elections supercharged those warnings. Democrats won every closely-watched election, mostly by huge margins. They also posted gains among Latinos, voters under 30 and those who lack college degrees — a particular point of weakness for the party during the Donald Trump era.

That means that the newly drawn Republican districts, which were crafted with the presumption that comparatively strong 2024 GOP margins would carry over into 2026 — a year when Trump’s not on the ballot — look a lot more vulnerable.

“Tonight is such a blowout so far that I wonder if it gives some Rs pause about redistricting in states that are still pondering it,” Kyle Kondik, managing editor of the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, wrote on X on Tuesday.

If they had paid attention to one election cycle way back in 1894, Republicans might have been able to avoid this. That year, it was Democrats who lost a massive number of seats after taking redistricting too far. Still, their devastating losses, and their failure to give themselves enough cushion to weather political setbacks and hold onto some seats, contain some lessons for Republicans today.

In the 19th century, changes to maps were not just frequent but practically routine. “Between 1862 and 1896, there was only one election year in which at least one state did not redraw its congressional districts,” Erik J. Engstrom, a political scientist at the University of California, Davis, has found.

Parties would take power, draw a new map and then get blown out when the tides turned against them in subsequent elections; their dummymanders couldn’t withstand the pressure. Republicans picked up 64 House seats in 1872, only to lose 94 seats in 1874.

After the 1890 census, Democrats were able to redraw 148 House districts, compared with just 40 for Republicans. And they got greedy.

There wasn’t much margin for error. In those days, in contrast to today, large shares of districts remained competitive cycle after cycle. In the late 19th century, nearly 40 percent of House districts were decided by 5 percentage points or less. After the 1890 census, Democrats didn’t bulk up their more promising territories, instead maximizing the number of districts that were conceivably winnable.

But then came 1894, an especially tough year for the Democrats, who held the White House and both chambers of Congress.

The politics of that year in many ways resemble our own. The nation had a president, Democrat Grover Cleveland, who’d returned to power thanks largely to inflation, after having lost his first reelection bid. Congress was arguing about tariffs. And the president sent federal troops into Chicago over the objections of the governor of Illinois — in that case in response to a railroad strike. (As a conciliatory gesture, Cleveland signed a law that June creating the Labor Day holiday.)

As is so often the case, the overarching issue heading into the 1894 elections was the economy. The nation had suffered a severe recession, which was known retrospectively as the Panic of 1873 but at the time was called the Great Depression. The Democratic majorities in Congress were clearly in trouble. “The Democratic mortality will be so great next fall that their dead will be buried in trenches and marked ‘unknown’ — until the supply of trenches gives out,” said Maine Republican Rep. Thomas B. Reed, who stood to take the gavel when Democrats lost their House majority.

The maps Democrats had drawn in 1890 turned this setback into a bloodbath.

In Missouri, for example, Democrats had drawn maps that gave them 13 out of the state’s 15 House seats in 1892. After their share of the statewide vote in congressional races dropped by 6 percentage points in 1894, however, they lost eight of those seats. In New York, they lost 15 of their 20 seats that year. Throughout the Northeast, their total number of seats plunged from 44 to 7, while in the Midwest they lost 40 out of 44. They were reduced essentially to a regional rump party in the still solidly Democratic South.

All told, Democrats surrendered 114 seats at a time when the House had only 357 seats. They controlled no districts at all in 24 of the 44 states and only one in six other states. They would not regain control of the House for 16 years. Missouri Democrat Champ Clark, who later served as speaker under President Woodrow Wilson, called it “the greatest slaughter of innocents since the days of King Herod.”

In the wake of a depression, Democrats as the majority party were bound to pay a stiff political price. But by dummymandering, they’d made things worse. In his book Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy, Engstrom calculates that if they’d run in neutral districts — meaning maps were drawn so that the total number of seats won by each party would reflect its share of the statewide vote — Democrats would have lost 59 seats, not 114. Of course, they got clobbered in states where maps were drawn by Republicans, but they’d created problems for themselves by shaving their own margins too thin.

Things changed in the 20th century. Some states added restrictions to their constitutions that blocked mid-decade redistricting. Many dispensed with redistricting altogether — seldom or never drawing new lines for decades in an effort to preserve rural power as urban areas gained population. (Failure to redistrict at all, which became known as silent gerrymanders, was finally outlawed in the 1960s by a series of Supreme Court rulings that required equal representation.)

In 2019, the Supreme Court, found that partisan gerrymanders can’t be challenged in federal courts, flashing a big green light. At the dawn of this decade, however, the GOP’s overall strategy was still to avoid dummymanders. The party sought to lock in gains from the previous decade and widen their margins in seats they already held. “We want 10-year maps, not maps that are going to flip back and forth,” Adam Kincaid, executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, told me in 2022.

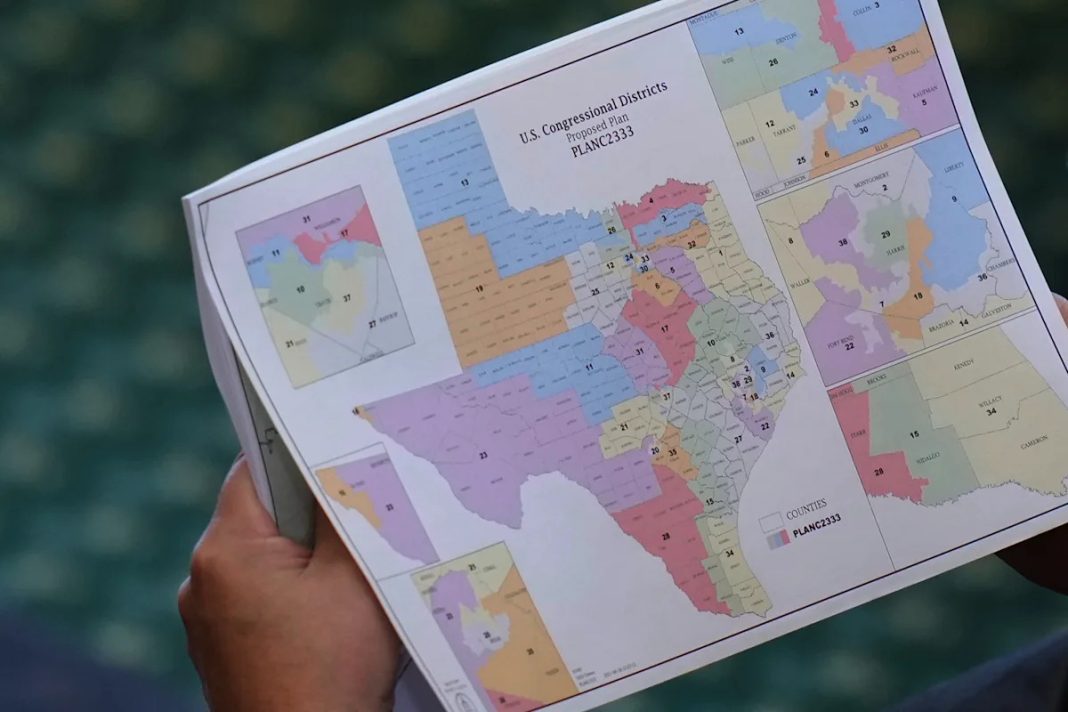

Just a couple of years later, the landscape has changed dramatically. Trump all but insisted that red states redraw their maps where any districts were theoretically still there for the taking, stating back in August that Republicans are “entitled to five more seats” in Texas.

Now, both parties are ready to grab at any chance they can get to improve their odds next year. And yet, by redoing their maps, Republicans run the risk of putting more seats in play, with Democrats eager to follow suit where they can. Both parties appear eager to go after advantages that may turn out to be temporary, if not total illusions.