Outgunned in the national redistricting war, Democrats are launching a multi-pronged legal battle to try and prevent GOP gains ahead of next year’s midterms.

It stands to be a grueling, lengthy and costly process for Democrats to counter President Donald Trump’s effort to draw new congressional maps that boost Republicans as they look to grow their slim majority next year. But with limited options to redraw maps in blue states outside Gov. Gavin Newsom’s effort in California, the courtroom presents the party’s best hope of countering President Donald Trump’s aggressive strategy.

The specifics differ from state to state, but taken together they will demonstrate some of Democrats’ long-held strategies in redistricting cases, namely arguing Republicans are suppressing voters of color and engaging in partisan gerrymandering with their proposed maps.

The courtroom challenges are largely organized by the National Redistricting Foundation, the legal arm of the National Democratic Redisctricting Committee — led by former Attorney General Eric Holder. The group declined to share how much it is prepared to spend on these cases, citing ongoing litigation, but is making an early and concentrated push with the tacit backing of Barack Obama, who headlined a fundraiser for the groups in August.

Legal challenges are “the final backstop,” said John Bisognano, president of the NDRC. “The courts are an underappreciated tool for fighting back to preserve our democracy.”

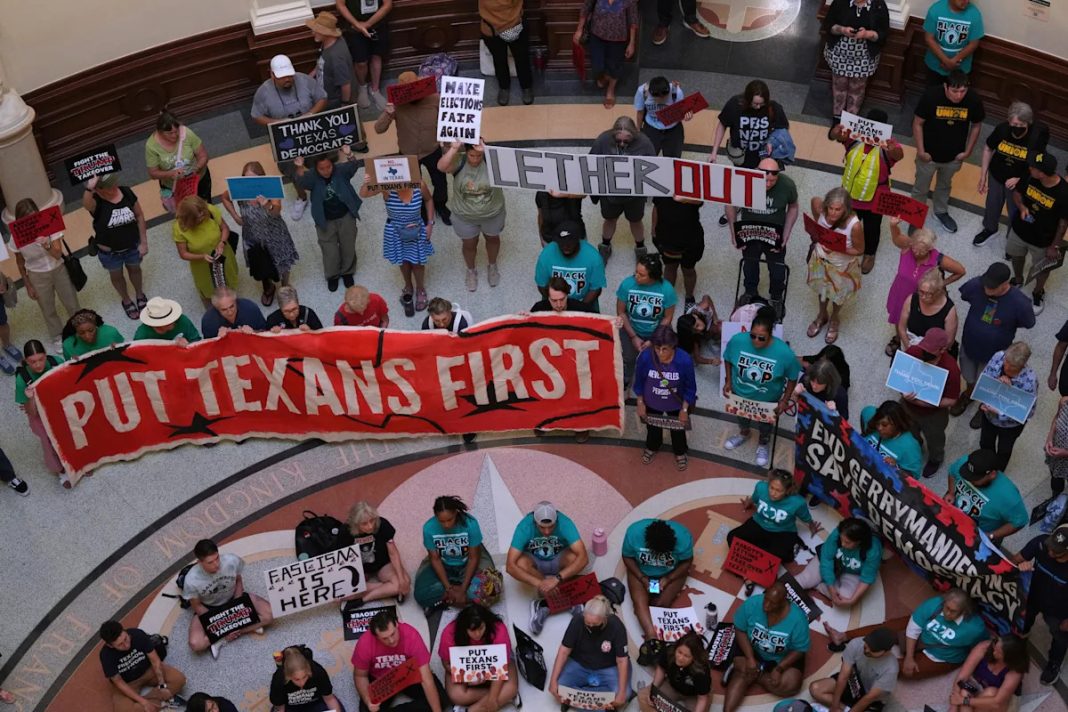

The machinations began last month, after Texas passed its new map carving out five extra seats for Republicans. The legal arm of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee — an organization affiliated with Obama — was quick to file suit challenging the Texas GOP’s alleged use of race in redrawing the lines. Additional lawsuits have quickly followed.

A judge is expected to decide by the end of October whether to grant a preliminary injunction on Texas’ map, a tight timeline that gives Democrats their best remaining hope so far at thwarting the GOP push before the map takes effect for next year’s elections.

Litigation also looms in Missouri and Ohio — where state lawmakers are redrawing their congressional lines — and potentially Florida and Indiana too, if those states move forward with their own mid-cycle map shuffles. And a recent ruling in Utah could give Democrats the chance to pick up one seat there.

The National Redistricting Foundation is involved in the Utah case that predates the ongoing redistricting war, and is planning for potential lawsuits in red states. The foundation was heavily involved in Alabama’s 2023 redistricting Supreme Court case, where the state agreed to pay $3 million to the plaintiffs for legal fees after justices determined the state was violating the Voting Rights Act by diluting the power of the state’s Black voters. The lawsuit resulted in a second Democratic-held seat in the state.

While the courts offer a glimmer of hope for Democrats seeking to thwart the Republican efforts, rulings in their favor are no sure thing.

“The path through the courts has always been an uphill battle,” said Justin Levitt, a law professor at Loyola Marymount who specializes in election law. “Litigation is slow and cumbersome and not anybody’s first best option ever.”

Past redistricting cases have been split for Democrats, especially after a 2019 Supreme Court ruling that limited the role federal courts play in partisan gerrymandering cases. That has left Voting Rights Act claims as their best chance in federal court, even as the Supreme Court is set to hear a case this fall that could gut key provisions of the landmark civil rights era legislation.

Perhaps nowhere are Democrats more familiar with the twists and turns of a prolonged legal battle than Ohio, where the prior map-making process was volleyed back and forth between the state legislature and courts for years. Ohio Democrats are gearing up for the likelihood of another fight as the state legislature begins the process of writing new maps, and they’re watching to see if the GOP reaches for three new seats – a configuration Democrats believe stands to violate requirements around how tightly the boundaries of districts can be drawn.

“Our legal team here will be monitoring the redistricting process very, very carefully, as we did the last cycle,” said Jocelyn Rosnick, policy director at the ACLU of Ohio. The organization will likely join any suit against Ohio’s effort as it did in 2021.

But this time around, Democrats are facing a more conservative composition of the state Supreme Court that could impede their success: Republicans have consolidated power on the court since the 2021 map challenge, and now hold six out of the seven seats.

An even steeper uphill battle in the courts has Democrats and fair voting groups considering another option in Ohio: mounting a referendum campaign to repeal whatever map Republicans in the state legislature settle on. That too would be an expensive and difficult undertaking, but the national attention on redistricting — and the Democratic party’s desperation to counter the GOP — would provide a boost.

Privately, Republicans see a legal path for Democrats to slow or even reverse their efforts in some places, but they also say court cases from the left are nothing new in redistricting fights.

“Their hopes are always in the courts, because that’s just where they go,” said one GOP operative, granted anonymity to speak candidly. “They have no problem funding hundreds of lawyers to these states to try and get a favorable ruling.”

Plus, Republicans have their own legal battles to fight in California, where the GOP has already tried to stop elements of Newsom’s ballot measure. On Thursday, Republican gubernatorial candidate Steve Hilton sued the state over its ballot measure, saying the proposed map violates federal law by not having districts with equal populations.

Across all the cases, the clock is ticking. With 14 months before the midterms — and far less time until filing deadlines and primaries — decisions need to come fast. If they don’t, Democrats risk the new maps staying in place for next year’s elections, which will determine whether they can reclaim any national power after last year’s drubbing.

“Litigants in Texas and litigants going forward, will be sort of trying to beat a clock where they don’t know what the numbers are,” said Levitt, the law professor. “If it’s a countdown clock, they don’t know how much time is left. They just know at some point that court action is likely to be paused because of the coming election.”

Elena Schneider contributed to this report.