Stephanie Shah kept her eyes on the winding road as rain streaked across the windshield. Her husband, Binod Shah, sat in silence beside her, staring out the window. It was late evening in Washington state on 23 March, and they had been driving all day, trading shifts, barely speaking, while their nine-month-old son dozed beneath a blanket in the backseat. The sky hung low and gray, and evergreens, soaked and still, stood witness along the road. Inside the car, a Nepali-Christian folk song played quietly on repeat. At some point, Binod reached over and rested his hand on Stephanie’s leg. It wasn’t reassurance. It felt more like a final touch.

When the baby started to cry, Stephanie pulled over and together they changed his diaper, working without words. Then Binod leaned down, kissed his son’s forehead, and began to cry.

That’s what I’d always been told: that if you follow the rules, things work out

Stephanie Shah

As they got back on the road, Stephanie’s mind raced with thoughts she did not dare say out loud: “What if I just turned around? What if I drove him to Mexico and we disappeared?”

She tried to picture this alternative life on the run. But she had grown up in a strict, conservative Christian household. Obeying the law wasn’t just a rule – it was a commandment of the Lord.

“That’s what I’d always been told: that if you follow the rules, things work out,” she said.

After hours of driving, and a futile stop at the Canadian border, the road narrowed. Ahead, floodlights lit up a chainlink fence, and a gray concrete building came into view – the quiet machinery of a government at work. Google Maps’ robotic voice broke the silence, confirming they had arrived at the Northwest ICE processing center in Tacoma, just outside Seattle, Washington.

Stephanie parked the car and kissed Binod goodbye. His deportation to his country of birth, Bhutan, triggered by a criminal conviction, complicated by his refugee status and enabled by an aggressive anti-immigration machine, would shatter their life and shake the political convictions of Christian conservatives in Twin Falls, Idaho.

Making a new life in Idaho

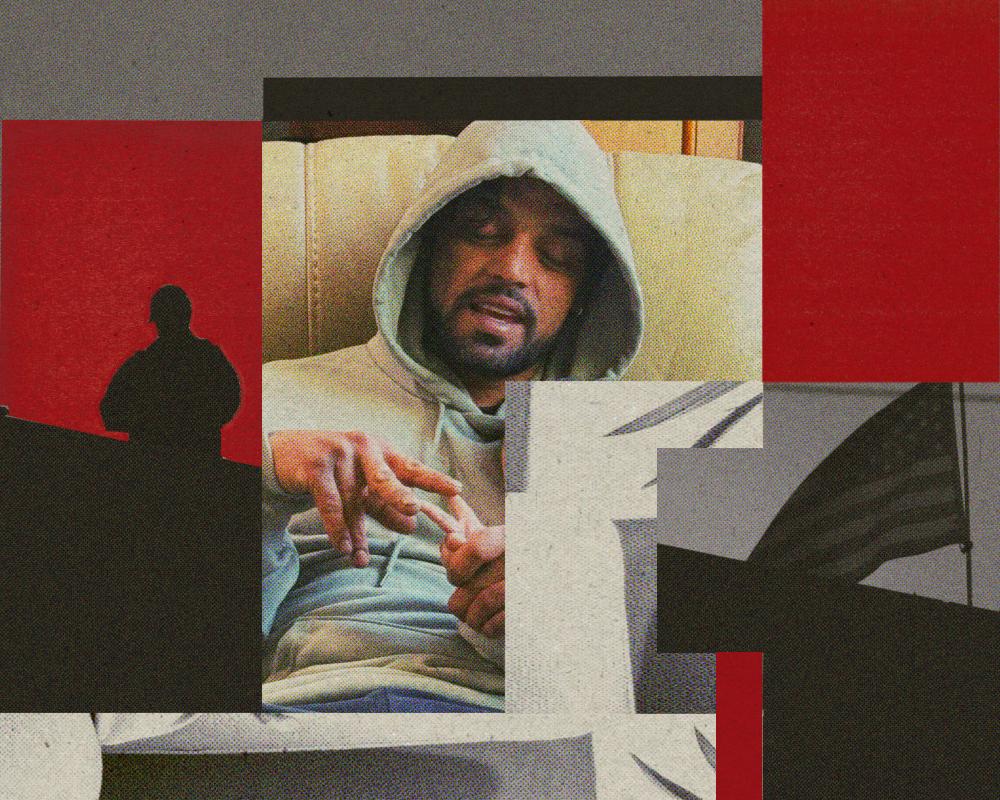

Stephanie, 35, grew up in Blackfoot, Idaho, where her father was a minister and her mother homeschooled the children. Most of her neighbors were Mormons, while her family belonged to a small evangelical congregation. “You don’t think of someone like me as a religious minority, but I was,” she told me in one of multiple phone interviews. Binod, already in hiding in south Asia, was only able to speak to me through Facebook Messenger.

At 18, Stephanie joined a Christian ministry that took her to Uganda and later Indonesia, where she taught English for two years among Indigenous communities and at an orphanage. When she returned to Idaho, she enrolled at Aletheia Christian college, about 10 miles north of Twin Falls. There, the college’s founders, Pastor Randall Davis and his wife, Dr Diane Davis, who is also a professor at the college, introduced her to the growing Bhutanese refugee community in Twin Falls, including a young man named Binod Shah.

Related: A US haven for refugees was divided over Trump – now immigration crackdown has left a ‘community breaking’

Binod’s upbringing was nothing like hers. Binod, now 40, was only four when Bhutan expelled more than 100,000 Nepali-speaking Lhotshampa in the early 1990s under its “one nation, one people” campaign. The policy stripped many ethnic minorities of their citizenship, banned the Nepali language in schools, and criminalized dissent, with brutal military crackdowns against those who spoke out. Human Rights Watch and other international groups later described the expulsions as a form of ethnic cleansing.

Like most Bhutanese refugees, Binod’s family spent years in camps in eastern Nepal, living in bamboo huts behind barbed wire, with rationed food and water and no electricity. After years of failed repatriation talks, in 2007 the United States began a resettlement program and by 2016 had accepted more than 86,000 Bhutanese refugees. While most ended up in Ohio and Pennsylvania, some went to Twin Falls.

Twin Falls sits in Idaho’s southern Magic valley, a city of more than 50,000 that is about 75% white. Conservative and deeply Christian, the town has consistently voted Republican, backing Donald Trump in both 2016 and 2024. Yet since the 1980s, it has been one of only two cities in Idaho, along with Boise, to accept resettled refugees: first south-east Asians, then eastern Europeans from the former Soviet bloc, Bosnians in the 1990s, and later families from Africa and the Middle East. In 2008, Bhutanese families like Binod’s joined this stream of newcomers, drawn by Twin Falls’s affordable housing, agricultural jobs and schools that offered an ESL program to refugee students; about 150 Bhutanese refugees live there now.

For years, the system worked: adults found steady jobs on dairy farms, and children settled into local classrooms. But in 2016, as Trump’s first presidential campaign stoked fears about immigrants and Muslims, Breitbart and other rightwing news outlets exaggerated reports that refugee boys had raped a young girl in Twin Falls, igniting protests, militia activity and a wave of anti-refugee sentiment across the city. The outrage quieted during the Biden years, but resentment never fully disappeared. In the lead-up to the 2024 election, a small group of Trump supporters demonstrated outside the refugee center.

Binod took on multiple jobs after his arrival in Twin Falls, and was on the path to permanent residency: under US law, refugees can apply for a green card after one year in the country and citizenship after five. “Binod was always working,” Randall remembered. “Washing dishes at a Chinese restaurant one day, working in a gun shop the next. He was sharp and relentless.”

When Stephanie pursued a master’s degree in intercultural communication, focusing her thesis on Bhutanese Hindu communities in Twin Falls, Binod became her translator. His ease with people drew her in, and their conversations often stretched long after the work ended. They spoke about their childhoods: Stephanie grew up in a tight-knit community, yet often felt out of place; Binod had come of age in a refugee camp, stateless and uncertain of his future. Faith also tied them together. Stephanie had been raised Christian, while Binod came to it later, eventually joining a church in town where Randall and Diane held leadership roles and many refugee families attended service.

Sometimes, the conversations turned to politics. Stephanie, a conservative, says her moral compass was set by belief in scripture, strong borders and opposition to abortion. “Binod liked playing devil’s advocate when we talked about politics,” she recalled. “He did agree with some of Trump’s policies, especially on the economy.”

Then one snowy day in January 2020, Binod surprised her. “We should make this official,” he said. It wasn’t a question about dating. It was a proposal.

Stephanie had prayed since she was 14 for a husband who was hardworking, charismatic, unafraid, relentless, devoted. “Binod had all of them,” she said.

Her father, who had met Binod in ministry trips to Twin Falls, gave his blessing quickly. He told his daughter: “I’m way more OK with this than I thought I would be.”

Caught in Trump’s dragnet

However, Stephanie did not go into the engagement blind, and Binod’s past was no secret. In May 2017, Binod was arrested in Twin Falls after an altercation with his first wife, who told police he had threatened her with a knife, according to reporting from East Idaho News and available court documents. Binod denied holding a weapon but pleaded guilty to felony aggravated assault the following year, by which time the couple had filed for divorce. At sentencing, the judge called the incident “disturbing” and ordered five years of probation along with 90 days in jail.

“They said, if you go to trial, you’ll get 10 years, but if you take the plea bargain, you’ll get 90 days,” said Stephanie. In the US, an estimated 98% of criminal convictions come through guilty pleas, according to the American Bar Association, a system critics say disproportionately harms immigrants, the poor and those with limited access to legal counsel.

[Refugees] came here legally, and the US government determined they had a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country

Miriam Hayward

“Even though Binod had been here for a decade, his English was still rough. He didn’t fully understand what pleading guilty meant,” Stephanie said.

Randall put it in starker terms: “The attorney told him to take a plea deal without explaining that he was walking straight into his life sentence.”

Binod’s public defender and the district attorney who tried his case did not respond to requests for comment.

Binod’s criminal conviction triggered deportation proceedings, and he lost his green card. In 2019, an immigration judge ordered him removed from the US.

“If you’re undocumented, you can be arrested at anytime – regardless of whether you have a criminal record or even if you’ve performed heroic service,” said Miriam Hayward, a retired immigration judge from San Francisco. “Refugees are different. They came here legally, and the US government determined they had a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country. They’re on a pathway to citizenship. But that doesn’t mean they can’t be deported.”

Major and minor convictions alike, such as shoplifting or driving under the influence, are grounds for deportation, including for green card holders and refugees, says Dr Julia Gelatt, associate director of the US Immigration Policy Program at the Migration Policy Institute. Gelatt also stressed that under US law, “people shouldn’t be sent to a country where they face a credible fear of persecution or torture,” as would be the case for many refugees.

Binod was detained by ICE for nearly nine months, but Bhutan, which had long denied repatriation requests, refused to accept him. ICE eventually released him under supervision. In October 2020, Stephanie and Binod married.

“I looked up his record. I prayed. I talked to my parents. I spoke with mentors and people I trust,” Stephanie said. “I knew the risk, but I also knew that we were called to be together.”

Before meeting Stephanie, Binod had been learning to fix cars in his sister’s garage. Upon release, he began volunteering his mechanical skills around town, often helping those who could not afford repairs. Diane Davis remembered one winter night when a tourist got stranded in the snow while driving to Las Vegas, and a police officer towed the car to Binod’s garage. “Binod not only fixed it,” Diane said, “he stayed up all night working on it and never charged a cent.”

In January 2021, Stephanie and Binod registered Shah Automotive in Idaho. “We were a good team,” Stephanie said. “Binod was incredibly skilled, and I enjoyed handling the administrative side.” But trouble returned. In 2022, Binod was arrested for felony DUI and sent to North Idaho correctional institution in Cottonwood. He was released in April 2023, and though his parole officer recommended early discharge for good behavior – “Binod had maintained sobriety and demonstrated a positive lifestyle,” wrote the officer – his probation was extended to 2027.

Back in Twin Falls, Binod and Stephanie bought a house, went to church, and began talking about having a child together. They cared for Binod’s two children from his previous marriage, while expanding their auto shop, hiring local mechanics and offering special discounts to refugees and veterans.

That is how Jackson Stewart, 25, came to know Binod. His parents’ car broke down in town, and when they told Binod their son was looking for mechanic experience, he offered an internship without hesitation. “He took a chance on me,” Stewart said. It paid little, but Stewart learned a lot. “He was a great teacher and a great leader. He always made jokes and made us feel comfortable.” In October 2024, Stewart proudly posted on Facebook that he had completed his second engine removal.

Weeks later, Trump was elected president again, after campaigning on the promise of ruthless mass deportation of undocumented people in the US, particularly those with a criminal background. In Idaho, he won 67% of voters, including members of Stephanie’s family (Stephanie declined to say how she voted). Randall and Diane voted for Trump, as did Stewart and many of Binod’s customers and co-workers. In spite of the looming deportation order, they did not think Binod, a refugee, would be caught in Trump’s anti-immigrant dragnet.

Within hours of taking office in January, Trump signed executive orders halting refugee admissions. His administration moved to end birthright citizenship and vastly expanded anti-immigration enforcement. Soon, ICE raids spread beyond workplaces and homes into restaurants, courthouses and even hospitals.

In early March, the Shahs received a phone call from an ICE agent ordering Binod to appear for removal proceedings. Binod, believing his cooperation might make a difference, got ready to make the drive to the ICE center in Tacoma. Stephanie, meanwhile, hoped that the immigration judge would take the letters of support from Twin Falls neighbors and community leaders – 16 had been written on Binod’s behalf – and the parole officer’s positive report into consideration and see that “he deserved a second chance.”

“He always did what the court asked of him,” Stephanie said, her voice firm. “The law can be strict, but we have to remember the human condition. We have to have compassion.”

Watching the current administration’s mass deportation strategy has been damaging to refugee protection

Kelly Ryan

But before they left, Binod broke down, telling Stephanie that he feared never seeing her or their son again – the situation in Bhutan was dangerous. Stephanie’s mind whirled. Tacoma was close to the border. If Binod could “self-deport” and seek asylum in Canada, there was a chance he could avoid being sent back to Bhutan. They detoured their drive to try but were refused at the crossing by Canadian officers, who walked Binod back into the US, where border patrol officers processed him.

Behind the wheel, Binod by her side once again, Stephanie pointed the car towards Tacoma.

On 3 June, more than two months later, the worst happened. Binod called Stephanie from an ICE agent’s phone: he was at the New Delhi airport, about to board a flight to Bhutan. ICE had begun deporting resettled Bhutanese refugees – a move Bhutan briefly complied with, only to immediately expel them to the Indian border.

“Watching the current administration’s mass deportation strategy has been damaging to refugee protection,” said Kelly Ryan, president of Jesuit Refugee Service USA, who formerly worked at the state department’s bureau of population, refugees and migration. “US law does recognize that people who commit crimes can be subject to removal, and we’re not disputing the wisdom of that law. What we’re saying is that people are being sent back to situations where they can’t work, integrate locally, gain citizenship or access territorial rights – effectively rendering them stateless after having held status in a first country of asylum.”

ICE confirmed to the Guardian in a statement that Binod was removed from the US on 31 March due to his criminal record. “Let me be clear, illegal aliens who commit heinous crimes in this country will be swiftly removed from American communities,” said Emily Covington, assistant director in the ICE office of public affairs. ICE did not respond to questions regarding the safety of sending refugees back to countries from which they were expelled.

According to Pew, nearly 97% of Americans support deporting those who have committed violent crimes; it is a bipartisan policy. It is also a process that turns one sentence into two: people serve their time, only to be handed over to ICE for deportation. Justice advocates call it a “double punishment” that treats immigrants as disposable even after they have paid their debt to society, and argue for limited cooperation between state prisons and jails and federal immigration authorities.

Stephanie could hear the noise of the terminal behind Binod, the heaviness in his breathing, as he prepared to return to the same country that had uprooted him and tortured and imprisoned thousands, including his father. “He loved this country, America, more than anyone else,” she said, “but he’s the one who was deported.”

Reckoning in a Christian community

Something was off when Jackson arrived at Shah Automotive at 7.30am on 4 June. Stephanie looked shaken; the shop was quiet.

Stewart and his co-workers had assumed Binod would be released by the immigration judge, “because of his legal documentation and because of the kind of person he is”. A devout Christian raised in a church that welcomed refugees, Stewart saw Binod as a model of faith and family. The news of his deportation stunned Stewart: “At first, I didn’t have much to say. Later that day, I cried.”

Randall has known Binod for more than 16 years. A self-described conservative constitutionalist Christian, he blames Joe Biden for Binod’s deportation. “Biden was completely responsible for it. Trump wasn’t,” he said. In Randall’s view, Trump was “just fixing the border”, cleaning up after Biden’s failure to control immigration, and Binod was collateral damage.

He later described Binod’s deportation as “ICE’s mistake” too: “The way they’ve handled it, I don’t like it.”

Binod bore the consequence of breaking the law with his DUI, says Randall, but he does not believe Binod received a fair trial for the aggravated assault conviction that triggered his deportation. Nor does Randall think accountability entails sending refugees back to the country that made them stateless in the first place. He references the Bible: “Care for the widow, the orphan, the poor, and the refugee.”

He was emphatic about one other point: “Refugees aren’t illegal. I wish they’d stop calling refugees illegals.”

Diane, who regularly visits the Bhutanese congregation in Twin Falls and mentors refugee Christian youths, sees refugees as “adopted children” of the United States. “When you adopt a child, you don’t do it with the plan of sending them back,” she said. The breakneck speed of deportations under Trump – more than 340,000 since January – troubles her. She believes that if refugees were given adequate instruction on the US legal system, many deportations, including Binod’s, might have been avoided.

Diane wrote letters to Idaho’s governor and to Trump demanding Binod’s return. She was “disappointed” by the governor’s response – a form reply – and noted that the White House never replied.

Related: US will limit number of refugees to 7,500 and give priority to white South Africans

By early August, more than three dozen Bhutanese refugees from across the US had been deported to Bhutan. According to recent reports, they were immediately told by Bhutanese authorities to leave the country. Some who made their way to refugee camps in Nepal were arrested by Nepali police and processed for deportation back to Bhutan. A Nepali news outlet reported that on 17 August one of the deported Bhutanese refugees had died by suicide in a camp. Others have gone into hiding, including Binod.

Facing customers at the auto shop who still asked for Binod was the hardest part for Stewart: “I had to tell them he was gone.” Eventually, he quit. Now he is looking for candidates, Republican or otherwise, who support less harsh immigration policies: “Trump is painting with too broad a brush … covering parts of the canvas that don’t need to be touched, people who don’t deserve to be smothered by the pain of ICE.”

“There’s a sense of loss we’ve all felt,” said one longtime customer, Mike, who asked to use a pseudonym due to his own immigration status. He described Binod as a supportive neighbor.

At the church where Binod worshiped, the congregation still reads from Matthew: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” One church member, who asked to remain anonymous because he did not want to risk starting conflict with family members who are Trump supporters, said: “What the Trump administration has done to the Shah family by deporting their father is not Christlike.” An October survey by New York Times and Siena University found that 52% of voters disapprove of how Trump has handled immigration, while 46% approve.

Overnight, Stephanie became a single mother with a business to run. Skilled mechanics are scarce; she has had no luck replacing Binod. She supported much of Trump’s economic policies and promises to cut the size of government, and his efforts to deport undocumented immigrants with criminal records, but has grown disillusioned. “Republicans say they’re about family values, about keeping families together. But what about my family? What value is there in tearing a father away from his wife and baby?”

What do we ask of immigrants as born Americans? What makes someone a ‘good immigrant’?

Stephanie Shah

She calls the immigration crackdown political theater. “Trump kept saying he’d go after dangerous criminals, but instead, he went after easy targets – people working hard, paying taxes, living quietly. Meanwhile, Trump keeps pardoning drug lords.” (Trump has pardoned multiple convicted drug dealers.)

Her faith in conservative ideals was challenged by a system that offered no redemption to her husband. “This is a second punishment for the same crime.” She just wants him to come home.

Several people from town and church have told Stephanie they are “not gonna vote the same way next election”. “People who’ve been conservative their whole lives are even showing up at liberal protests against ICE raids,” she said, referencing an uptick in anti-ICE demonstrations in and around Twin Falls. On a national scale, voters disapproved of ICE’s tactics by a margin of 56-39%, though Republicans approved by a wide margin, according to a June Quinnipiac poll.

Now Binod is trying to evade local law enforcement somewhere in south Asia; Stephanie will not say where. When reached through Facebook Messenger, he sounded weary. He said his wife should speak for him, believing her voice, as a white woman in the US, carries further than his.

“What do we ask of immigrants as born Americans? What makes someone a ‘good immigrant’?” Stephanie said. “Binod owned a business, employed Americans, went to church, raised a family, and worked to assimilate. Republicans get mad when people don’t assimilate. But Binod did, and it still wasn’t enough.”

They talk when they can, usually over Messenger. When he calls, she is putting their son, now one, to sleep. She holds up the phone so the boy can see his father’s face. Then the screen freezes, goes dark, and the connection is lost.