In Nepal’s capital, young would-be voters line up enthusiastically to register for the first elections since deadly anti-corruption protests toppled the government, the worst unrest in decades.

For many, it will be their first time participating in an election, and they see it as a chance to shape the future of their country of 30 million people, burdened by deep economic woes.

At least 73 people were killed in the September 8–9 protests that left parliament, courts and government buildings in flames.

The unrest was triggered by a brief ban on social media but fuelled by long-standing frustration over economic hardship and corruption.

Within days of the government’s collapse, 73-year-old former chief justice Sushila Karki was appointed interim prime minister to steer the Himalayan nation until elections on March 5, 2026.

“The pillar of this new government is built on the dead bodies of students,” said student Niranjan Bhandari, 21, as he waited to provide biometric data to complete his registration.

“That’s why, in the upcoming election, we want to uproot the old faces who have been clinging to power for too long,” he added.

“I’m here to register for my new voter identity card for that very reason.”

– ‘Growth to decline’ –

Nepal’s political future hangs in the balance.

The challenges ahead to ensure elections pass off smoothly are huge — including deep public distrust in Nepal’s established parties.

It remains unclear whether protesters and youth will try to form their own party, or if old politicians will seek to return.

The government has imposed a travel ban on KP Sharma Oli, the 73-year-old Marxist who served as prime minister four times before he was forced from power, as a commission investigates the unrest.

But Oli remains outspoken, calling for the reinstatement of the parliament “that was unconstitutionally dissolved”, in an address to supporters earlier this month.

The unrest also battered Nepal’s already fragile economy, where the World Bank estimates a “staggering” 82 percent of the workforce is in informal employment, with GDP per capita at just $1,447 in 2024.

The bank this month updated its economic assessment for Nepal, warning that “recent unrest and heightened political and economic uncertainty are expected to cause growth to decline” to 2.1 percent.

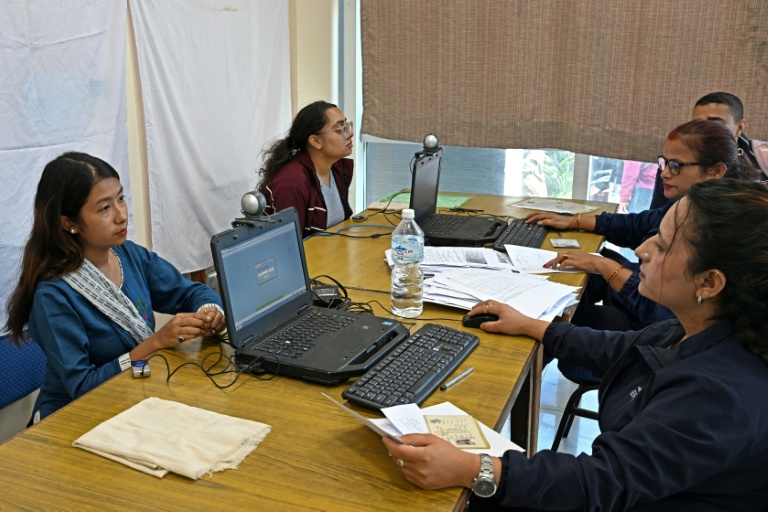

But at a district Election Commission office in Kathmandu, the excitement among the younger generation is clear.

“I’m really excited,” 20-year-old student Sambriddhi Gautam told AFP. “This will be my first time participating in an election.”

Gautam, who is studying to be a chartered accountant in neighbouring India, said she had returned to register to make sure she can take part.

– ‘Good of the nation’ –

Samiksha Adhikari, 32, a business consultant, waited to apply for her voter identity card.

“We need to bring in new faces who can stop corruption and make the country better,” she said.

“That’s why I’m here. I want to cast my vote for those who truly work for the good of the nation.”

In Nepal’s last general elections, in 2022, nearly 18 million people were registered to vote.

All Nepalis aged 18 and above are eligible to vote, with the deadline to register ending in November.

Sirjana Rayamajhi, 38, spokesperson at the district election office in Kathmandu, said she had not seen such enthusiasm before.

In her office, an average of nearly 400 people had been registering every day — four times higher than in past elections.

“The turnout is very high,” she said.

“Gen Z have come here to register their names with a lot of excitement. They want a new generation to bring change to the country. These days, the queue is only them.”

str/pjm/abh/mtp