Vaccination coverage is eroding across the United States at the same time measles cases are surging, according to new county-level data compiled from state health agencies.

Measles outbreaks are infecting more people this year than in any year since the early 1990s and have already killed three. So far in 2025, all but eight states have reported measles cases, a disease the U.S. declared eliminated in 2000. Nearly 92% of these cases were among the unvaccinated or people with unknown vaccination status.

Federal data released in July showed that childhood vaccination rates, which had remained steady for years, have declined, while the share of children exempted for religious and philosophical reasons has increased.

“What we see is that as trust erodes, as vaccination rates drop, the first thing that you see are measles outbreaks,” said Adam Ratner, a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Infectious Diseases.

Ratner said the outbreaks should act as a public health warning system, signaling that other diseases could follow.

“You have to look beyond that, because the diseases that are also vaccine-preventable, but maybe are a little less contagious than measles, are the ones that you’ll see after that,” he said.

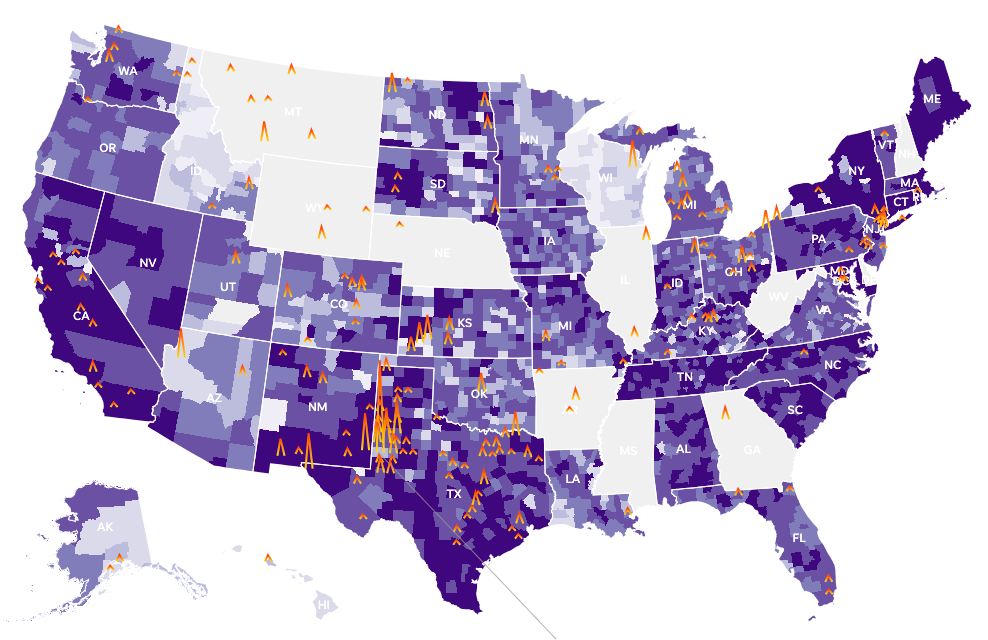

To assess coverage at the local level, Johns Hopkins University compiled data from state health agencies that, in the absence of a federal database, sheds light on how vulnerable communities are to outbreaks. USA TODAY later expanded this effort by adding data for states missing from the university’s database and filling gaps.

An analysis of this combined data, covering counties in 41 states, showed that routine vaccine coverage among children has slipped in most counties, leaving more communities vulnerable today than before the pandemic.

In at least three out of four counties, vaccination coverage is below 95%, an immunity threshold experts say is needed to prevent widespread outbreaks.

“The fact that there are so many counties below this threshold means there is a lot of exposure risk,” said Lauren Gardner, director of Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering.

“It doesn’t mean there’s definitely going to be an outbreak, but the risk is higher if a case is introduced in a community,” she added.

Experts also warn that when coverage falls below 90%, the risk of outbreaks rises sharply. Children who are immunocompromised or too young to be vaccinated rely on community immunity, they say.

Today, about 63% of counties meet that minimum threshold, compared to 84% before the pandemic.

The data, together with interviews with public health experts, underscore that skepticism around the COVID-19 vaccine has seeped into broader attitudes toward immunization, worsened by the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

Vaccine skeptics falsely claim that the measles vaccine causes autism, a claim repeatedly disproven by extensive scientific research. Regardless, rising vaccine skepticism has discouraged parents from vaccinating their children against dangerous diseases.

A September Kaiser Family Foundation–Washington Post survey found that 9% of parents believe the false claim linking the MMR vaccine to autism, and nearly half are unsure what to believe. About one in six parents reported delaying or skipping vaccines (excluding seasonal flu and COVID-19), often citing safety concerns or distrust.

Parents who identify as Republican, younger, or homeschool their children are among the most likely to delay or skip vaccines, the survey found.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends two doses of the MMR vaccine for children: first at 12–15 months, then at 4–6 years. The agency also recommends vaccines for polio, chickenpox, and hepatitis B, a viral infection affecting the liver.

Public health experts say these recommendations are facing challenges under Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an outspoken vaccine critic. Kennedy fired all 17 members of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in June, replacing some with vaccine skeptics.

The ACIP has already changed the MMRV (measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella) vaccine schedule, removing the recommendation for children under 4. The committee also considered changes to hepatitis B recommendations, but a vote was delayed.

Experts warn these shifts could add confusion and further erode vaccination rates, even as clarity on vaccine safety and access remains critical.

To that end, Ratner said, granular data collected by Johns Hopkins University and USA TODAY is important for identifying vulnerable populations.

“Often people will look at state rates, which are important,” Ratner said. “But really what we find is that what matters is much more local rates — at the level of the county or even smaller.”

The Johns Hopkins University-USA TODAY data is based on county-level vaccination compliance among kindergarteners — and, in a few cases, K–6 or K–12 students — covering either MMR vaccinations or all doses required for school enrollment.

There are caveats: record collection varies by state, so state-by-state comparisons should be made cautiously. Because some agencies track students’ compliance with vaccine requirements — not actual vaccination status — the true vaccination rate could be lower than reported in those instances.

For example, Oregon excludes exempted students in completion rates, while Wisconsin doesn’t.

“A student can be compliant with the school law either by being up to date on vaccines or by submitting a waiver, so school compliance rates could be higher than the vaccination rate of the school population,” said Jennifer Miller, spokesperson for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Measles once sickened millions of Americans and killed hundreds each year. In the 1960s, the U.S. launched its vaccination program, eventually eradicating measles before the turn of the century. By 1980, all 50 states had adopted school vaccine mandates, requiring children to be vaccinated before enrollment.

Measles is particularly dangerous because it can spread before symptoms appear. Even with a low fatality rate, the virus can cause lasting complications, including brain damage, neurological problems, and blindness.

As of September 30 this year, the U.S. has reported nearly 1,550 measles cases, surpassing totals from any outbreak since the early 1990s. Only 2019, when the disease spread through unvaccinated communities in New York, comes close.

The first outbreak in 2025 occurred in the Mennonite community in Gaines County, Texas, where vaccination rates are low. The virus then spread across West Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. Gaines County has reported 414 cases this year, nearly a quarter of the national total.

There, vaccination coverage among kindergartners has averaged around 82.4% in recent years, 12.6 points below what experts call community immunity.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 57% of counties were considered fully protected against outbreaks. That figure has since dropped to 25%.

The decline in coverage spanned nearly three-quarters of counties, with each experiencing an average four-point drop. Only two states, Connecticut and Maryland, now have every county above the immunity threshold, while nine in 10 counties in Maine and New York meet it. No counties clear the bar in Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Utah, or Wisconsin — the same states with high exemption rates.

In July, the CDC estimated that nearly 286,000 kindergarteners lacked proof of completing the MMR vaccine series during the 2024–25 school year.

Meanwhile, more parents are exempting their children from vaccination on religious or philosophical grounds, though medical exemptions have remained flat. Non-medical exemption rates rose to 3.4% in 2024–25, up from 2% a decade ago.

Even small increases can have a big impact, said Elizabeth Williams, senior policy manager at Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

“Every increase reduces the ability to reach the threshold that scientists believe protects the community,” Williams said.

Experts recommend keeping exemption rates below 5%, yet 17 states now exceed that level. Idaho leads at 15%, followed by Utah and Oregon at 10% each, and Arizona and Alaska at 9%.

“Rising exemption rates are concerning; especially if you work under the assumption that a child who has an exemption on file with their school is unvaccinated,” said AJ McWhorter, a spokesperson for Idaho Department of Health and Welfare.

“During a vaccine-preventable disease outbreak, then there are more children who would be at risk for contracting the disease and who would presumably need to be excluded from school,” McWhorter said.

Policy shifts may further lower vaccination rates. Many states have introduced changes that make it easier for families to obtain waivers. Florida plans to remove the mandate entirely from public schools.

Since 2021, lawmakers nationwide have introduced over 2,500 vaccine-related bills, almost half targeting requirements like mandates or school exemptions, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

These state-level changes, alongside the shift in federal guidance, continued misinformation and access challenges, will make the situation worse, epidemiologists at the Oregon Health Authority said in an email.

Public health is a community responsibility, Gardner, the Johns Hopkins expert, said. “Everyone has to be in on it, because otherwise it doesn’t really work.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: New maps reveal outbreak risks. Is your county protected?