Democrats trying to counter President Donald Trump’s red-state gerrymander are facing a roadblock. Fifteen roadblocks, actually.

That’s how many Democratic-led states have a political trifecta — the same setup that helped Texas Republicans push through new maps last month.

But of those 15, only California has made a serious effort to respond in kind — and even that initiative may fail at the ballot box. Leaders in 14 other states with a Democratic governor and state legislature find themselves unable to move forward, hampered by reasons ranging from constitutional limitations, legal deadlines and maps that can’t be gerrymandered anymore. In perhaps an acknowledgment of these hurdles, Democrats have turned to the courts to try stopping Republican efforts.

“It’s no doubt the case that it’s harder for Democrats to do this right now than Republicans,” said All About Redistricting author and researcher Douglas Spencer, an expert in election law at the University of Colorado.

The outlook for redistricting makes taking back the House a harder task for Democrats in 2026. They need to net three seats to reclaim the majority, a step they’ve framed as necessary to put a check on Trump and Republicans who lead the Senate. If Democrats don’t retake one of the two chambers, Trump will likely have two consecutive terms with single party control in Washington — something that hasn’t happened since George W. Bush two decades ago.

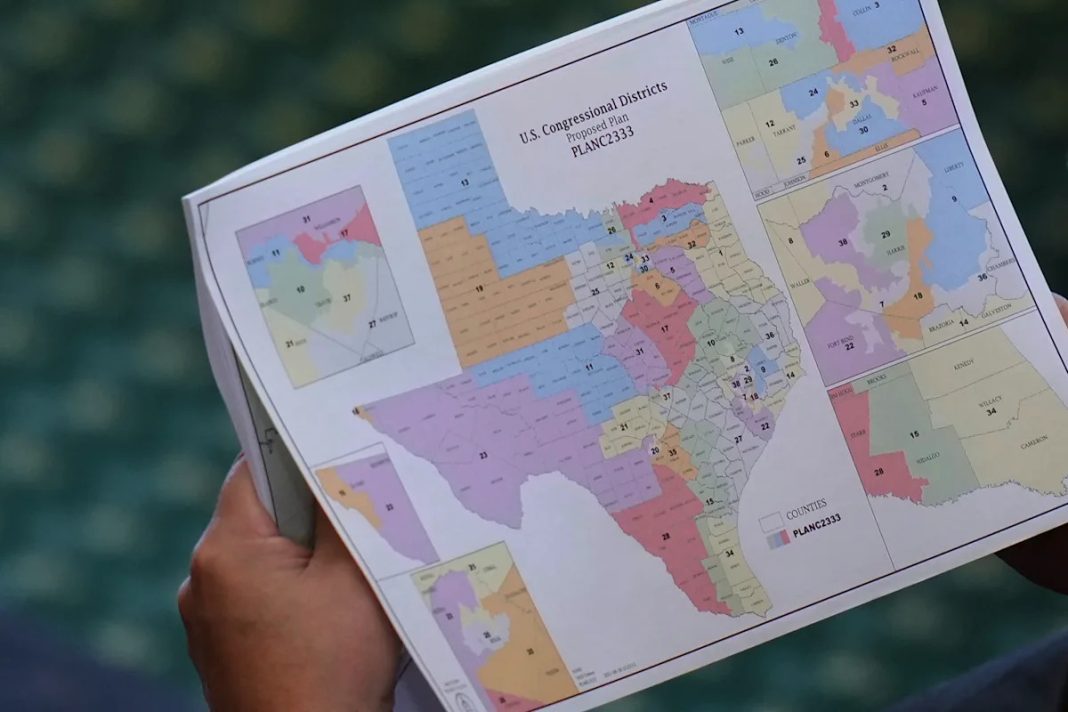

Republicans have been busy in recent weeks seeking to achieve that: Texas, Indiana, Missouri and Florida have all either redrawn their congressional districts or floated the idea, in hopes of adding new Republican seats to the House. At Trump’s behest, the Texas GOP added five seats favorable to Republicans. Texas, Indiana, Missouri and Florida all have Republican trifectas — where the GOP controls both chambers of the legislature and the governor’s seat — making it much easier to consider redistricting.

But of the 15 states with Democratic trifectas, only Maryland and Illinois’ legislatures have clear pathways to redraw lines that could make seats more competitive for Democrats. California and New York, meanwhile, can ask voters to change state gerrymandering laws to redistrict down the road.

So far, only California has moved on this: The state legislature, under pressure from Gov. Gavin Newsom, passed bills setting up a special election in November where voters will decide whether to replace the state’s congressional map. New York and Maryland signaled openness to redistricting, while some Illinois lawmakers are hesitant. Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker stopped short of ruling it out, telling reporters this month that he’s “pledged” to House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries “that I’ll do everything I can to make sure that Democrats win the Congress in 2026.”

Seven other states already have fully Democratic House delegations, leaving only Colorado, Washington, Oregon and New Jersey with Republican seats to spare. But those four have little they can accomplish because of state laws regarding redistricting and the political makeup of their state legislatures.

While new maps in Texas and California (if approved by voters) could cancel each other out by both adding up to five seats for each party in the House, the GOP’s additional targets of Indiana and Missouri could push Republicans a handful of seats beyond what Democratic states appear capable of flipping.

Even though California and New York have the legislative votes to change their state constitutions, Colorado and Washington do not.

“We don’t have the pathway to redistrict,” said Washington House Majority Leader Joe Fitzgibbon, a Democrat. “If our constitutional context were different, I think there would be appetite [to redistrict] in our legislature.”

Oregon and New Jersey do have legislative supermajorities, but face other hurdles.

The New Jersey Legislature missed the Aug. 4 deadline to send a ballot measure to voters this year, so would have to look to November 2026. Even then, Democrats already have a friendly congressional map that leaves few options to flip additional seats. Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy told reporters in late August that redistricting would “be very hard for us.”

Oregon has a Democratic supermajority, but not a quorum-proof majority — and strict constitutional laws that prohibit mid-decade and politically-motivated redistricting. Like Texas, where Democrats in the minority left the state to try procedurally blocking a vote on redistricting, Oregon law gives the minority party outsized power to hold up legislation indefinitely. Where Trump and FBI director Kash Patel approved a request to locate Texas Democrats who fled the state to avoid passing redistricting laws, there is little hope that the Republican administration would do the same if Oregon Republicans fled.

“It is not being taken as a real path here,” said a long-time Democratic consultant in Oregon who works closely with Democratic leaders and was granted anonymity to speak freely about the nature of the redistricting discussions. “There are just too many real overlapping hurdles.”

Washington, Oregon and New Jersey all require approval of both the state legislature and voters to change their state constitutions, so any redistricting efforts are dead in those states unless Democrats earn a supermajority in Washington or quorum-proof majority in Oregon in November 2026. Colorado has the lowest barrier to constitutional change: there, voters could mount a citizens’ initiative to do so, but it would take enormous grassroots effort and funding.

“It’s not technically impossible, but it is technically incredibly challenging,” said Colorado. Rep. Emily Sirota, a progressive Democrat who has sponsored state legislation related to voting and campaigns in the past.

As of September, there is no effort yet from voters. An initiative to give the governor emergency redistricting powers proposed in early August was withdrawn, and multi-millionaire Colorado businessperson Kent Thiry, who bankrolled Colorado’s 2018 measure to adopt an independent redistricting commission, says there may not be will among the voters to change it back so quickly.

“It is so sensible, and people react right away to the fairness of it, that we were able to win despite the political forces being against us from each party,” said Thiry, who also worked on the California measure. Thiry says Colorado voters could overturn his initiative, but believes it to be unlikely. “It would be expensive, and a lot of Coloradans would say ‘We don’t want to become a part of a race to the bottom.’”

The political culture of the West — in both Republican and Democrat states — is key to understanding the barriers to gerrymandering. Of the eight U.S. states with independent redistricting commissions, six are in the West. Three of those states are blue, two are red and one is purple — making it a nonpartisan issue.

University of Oregon Professor Chandler James, a Kentucky native who has spent the last few years studying political opinion in the West, says that fair redistricting laws fall in line with other “good governance” laws popular in the West like universal mail-in voting, non-partisan and open or semi-open primaries, ranked choice voting, citizens initiatives and ballot measures.

“It’s a part of a larger political culture where it’s just a little bit less bare knuckled,” James said. “[Which] emphasizes fair process and public engagement in the political system.”

Thiry, meanwhile, says the current push for gerrymandering has given him “existential depression.” But despite making an end to gerrymandering his life’s work, he also acknowledges the political reality: “While I will not be a part of any retaliatory gerrymandering,” he said, “I respect the people who decide that in this situation, they simply have to do that.”

Lisa Kashinsky and Brakkton Booker contributed to this article.