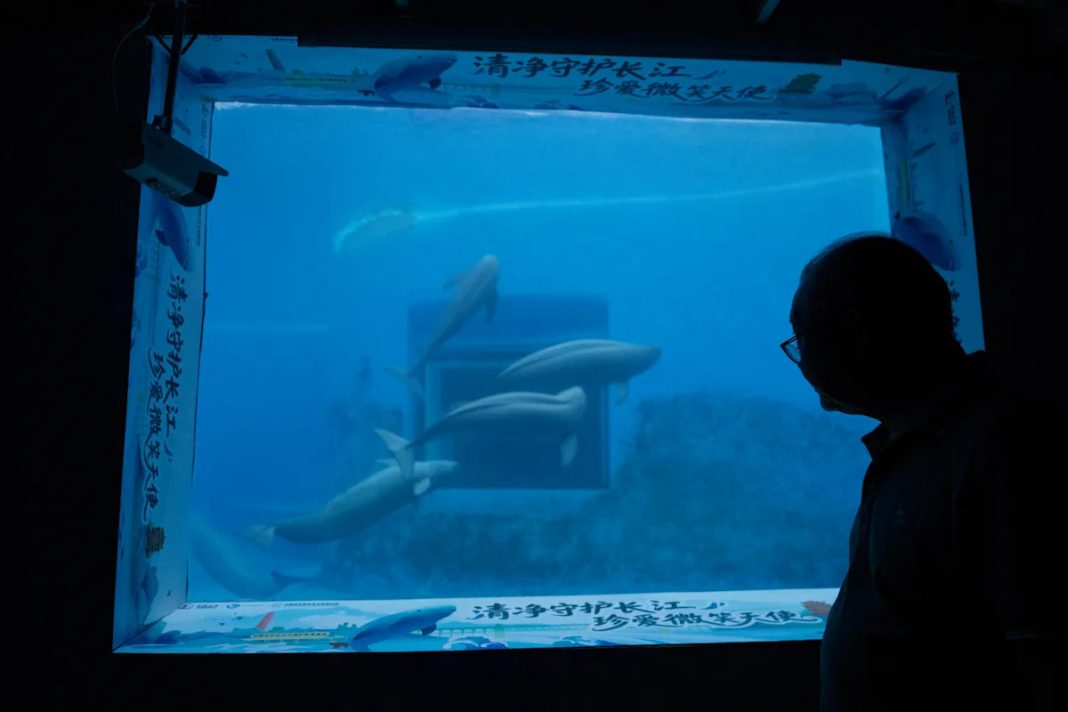

WUHAN, China (AP) — A dozen sleek grey Yangtze finless porpoises glide inside a vast pool at the Institute of Hydrobiology in Wuhan as scientists find ways to protect and breed the rare mammals in China’s longest river.

The Yangtze River is one of the busiest inland waterways in the world with 16 major ports. Cargo shipping volume along the river topped 4 billion metric tons (4.4 billion U.S. tons) in 2024, according to state media.

The finless porpoise has become a barometer of the river’s health. The population of the critically endangered species plunged from over 2,500 in the 1990s to just 1,012 in 2017 due to pollution, boat traffic and illegal fishing that depleted food supplies, researchers said.

The change alarmed the scientific community, including veteran researcher Wang Ding. He led an international team on a 2006 search for Baiji dolphins, another species that was nearing extinction. Despite a nine-day search, not a single dolphin was found and the Baiji was declared functionally extinct. The last captive Baiji dolphin hangs at a museum along with other rare aquatic species.

“We feared that if this animal cannot survive in the Yangtze, the other species will, like dominoes, disappear one by one from the river,” Wang said.

Conservation efforts sprung into place. The Yangtze River Protection Law was enacted in 2021, banning fishing for 10 years, relocating factories and prohibiting sewage and chemical runoffs into the river. Today, the population of Yangtze finless porpoises is edging upward at around 1,300.

To protect the Chinese sturgeon, also a critically endangered species, scientists began artificially breeding and releasing thousands of the fish into the Yangtze with the hope of restoring the wild population.

Scientists have called for additional measures to regulate shipping and for an extension of the 10-year fishing ban.

___

This is a photo gallery curated by AP photo editors.