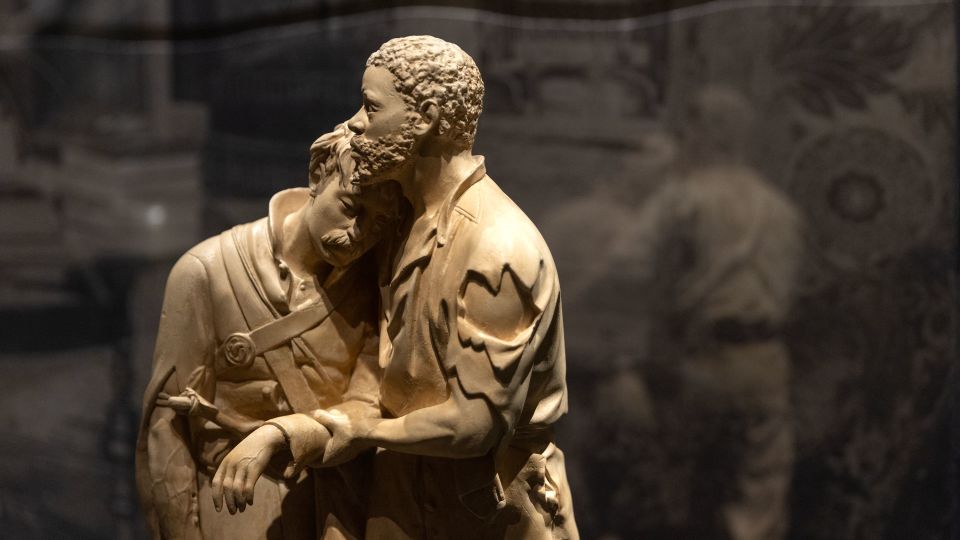

It is one of the most evocative works from the American Civil War: a sculpture of a Black man who had escaped from slavery helping an injured White Union soldier lost in hostile territory.

When it was unveiled in 1864, John Rogers’ “The Wounded Scout, a Friend in the Swamp,” was celebrated for its anti-slavery message and patriotic tone. But in 2025, a Smithsonian exhibition, “The Shape of Power: Stories of Race and American Sculpture,” asked visitors to reconsider the message behind the piece.

On display, the sculpture is paired with a description that prompts viewers to consider how the work, and others by Rogers “reinforced the long-standing racist social order,” despite its pro-Union and emancipation sentiment.

The exhibition’s efforts to challenge enduring ideas about race and American sculpture became a subject of President Donald Trump’s ire earlier this year. In an executive order, he condemned the exhibition for stating that “sculpture has been a powerful tool in promoting scientific racism,” that “race is a human invention” and that the United States has used race “to establish and maintain systems of power, privilege, and disenfranchisement.”

The Smithsonian’s American Art Museum shares a building with the National Portrait Gallery. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

“Museums in our Nation’s capital should be places where individuals go to learn — not to be subjected to divisive narratives,” the executive order said.

Trump has championed a cultural agenda built around celebrating, as the executive order put it, “shared American values” and “unmatched record of advancing liberty, prosperity, and human flourishing,” and he has put Vice President JD Vance, who serves on the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, in charge of stopping government spending on exhibits that don’t align with that agenda.

Meanwhile, the Smithsonian has begun a review of content in its museums, a spokesperson told CNN in a statement.

“The museum is committed to continuous and rigorous scholarship and research and unbiased presentation of facts and history,” the spokesperson said. “As such, and as previously announced, we are assessing content in Smithsonian museums and will make any necessary changes to ensure our content meets our standards.”

The review has raised serious questions over whether the world’s largest museum complex will curb candid discussions about the country’s past, beginning with exhibits like “T he Shape of Power.”

Anita Field’s “So Many Ways to Be Human” is displayed in the exhibition. In March, President Donald Trump issued an executive order calling for the Smithsonian to review content in its museums. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

A visitor touring the exhibition walks past Nicholas Galanin’s “The Imaginary Indian (Totem Pole).” – Tristen Rouse/CNN

Sasa Aakil, a young artist who was one of the student collaborators who helped with “The Shape of Power,” said that it would be “catastrophic” if the Smithsonian were to change many of its exhibits.

“America has never been good at truth. That’s why so many people are doing the work that they’re doing. That’s why this exhibition exists.”

Humbler displays, notable reactions

For the amount of attention it garnered from the president, the exhibition at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum has a surprisingly humble, intimate feel.

Tucked away on the third floor of a sprawling Greek revival building shared with the National Portrait Gallery in downtown Washington, the exhibit holds 82 sculptures dating from 1792 to 2023. The pieces are arranged according to a series of topics with prompts asking visitors to consider how they encounter the pieces.

“The Shape of Power” exhibit is on the third floor of the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum, which is in a sprawling Greek revival building that once served as the Old Patent Office building. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

A large passage of text on the wall at the exhibition entrance says: “Stories anchor this exhibition,” and that through it, visitors can discover how artists used sculpture to “tell fuller stories about how race and racism shape the ways we understand ourselves.”

The stated goal of the exhibit is “to encourage visitors to feel invited into a transparent and honest dialogue about the histories of race, racism, and the role of sculpture, art history and museums in shaping these stories,” its curators have written.

Ferdinand Pettrich’s “The Dying Tecumseh,” for example, portrays a Shawnee warrior’s death during the War of 1812. Completed in 1856, the warrior is shown in a relaxed pose, reclining as if asleep.

In reality, he died in battle and his body was mutilated by American soldiers.

Pettrich, according to the exhibit, made the sculpture as political propaganda for Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson, who had claimed he killed Tecumseh and made the alleged act part of his campaign slogan. It also reinforced racist ideas about Native Americans during a time when the United States was rapidly expanding west, the exhibition said.

Ferdinand Pettrich’s “The Dying Tecumseh” portrays the Shawnee warrior’s death during the War of 1812 in a fictional manner. The statue was housed in the US Capitol from 1864 to 1878, and was later transferred to the Smithsonian. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

Julia Kwon’s “Fetishization” represents a hollow, female torso wrapped in vibrant Korean cloth. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

A yard away from Hiram Powers’ “Greek Slave,” a famous 19th century sculpture, is Julia Kwon’s “Fetishization,” a 2016 work featuring a hollow, female torso wrapped with a vibrant patchwork of silk bojagi, Korean object-wrapping cloth. The intention, Kwon told CNN, is to comment “on the gravity and absurdity of the objectification of Asian female bodies.”

Asked about its objections to the exhibit, Lindsey Halligan, a White House official whom Trump has tasked with helping to root out “improper ideology” at the Smithsonian, told CNN in a statement: “The Shape of Power exhibit claims that ‘sculpture has been a powerful tool in promoting scientific racism,’ a statement that ultimately serves to create division rather than unity.”

“While it’s important to confront history with honesty, framing an entire medium of art through such a narrow and accusatory lens overshadows its broader cultural, aesthetic, and educational value,” Halligan said in a statement.

A visitor tours the exhibit, which features 82 artworks created between 1792 and 2023. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

“Instead of fostering dialogue or deeper understanding, the Shape of Power exhibit’s approach alienates audiences and reduces complex artistic legacies to a single, controversial narrative. After all, it’s hard to imagine Michelangelo thinking about racism as he chiseled David’s abs – he was in the relentless pursuit of artistic perfection, not pushing a political agenda.” (Michelangelo’s work is not part of the exhibit.)

Some see value in the president’s push to reshape the museums. Mike Gonzalez, a fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, expressed optimism about the Smithsonian’s review, arguing that the institution should not mount exhibitions that examine the US through “a prism of the oppressed and the oppressor.”

“I think, you know, you have to tell the whole story, not a small part of the story that is designed to make people feel grievances against their own country,” he said.

A book on the exhibit is sold in the museum’s gift shop. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

But critics say the administration’s review has the potential to undermine the nation’s ability to understand its complicated history through art.

Examining art from the past has the potential to hit at the core of how Americans understand their country, Northwestern University art history professor Rebecca Zorach told CNN, and that’s the value of exhibitions like “The Shape of Power.”

“Art provides ways to process these issues. I think some people are afraid of what it means to kind of have that opportunity,” Zorach said. The administration’s claims of a “divisive, race-centered ideology” are a “real caricature” of what museums and other cultural institutions are trying to do, she said.

It was also “astonishing” that the administration would dispute a scientifically accepted view that race is a construct, she added.

A woman views plaster portraits by artists John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

Probing questions

Aakil, the student collaborator on “The Shape of Power,” told CNN the exhibition was not designed to make people feel resentment toward their country, but to consider the broader context of the art.

She recalled the first time she saw “The Dying Tecumseh.” It unnerved her, she said, especially as she learned more about the distorted version of the history the artwork relayed.

For Aakil, the statue is a reminder that museums have always made some people uncomfortable.

“Many of these sculptures were always problematic, were always painful and were always very violent. And this exhibition is forcing people to see that, as opposed to allowing people to live in a fantasy,” the 22-year-old artist said.

The title of the exhibit is seen above Roberto Lugo’s “DNA Study Revisited.” – Tristen Rouse/CNN

Another piece, “DNA Study Revisited” by Philadelphia artist Roberto Lugo, is intended to push back against the ways sculpture has been used to bolster ideas about racial classifications.

In a self-portrait, Lugo uses different patterns that correspond to parts of his ancestry, drawing from Spanish, African, Portuguese and Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean.

Lugo told CNN he believes art is “a way for us to understand the world through someone else’s experiences.”

“Through exhibitions like this, I hope we can begin to normalize storytelling from diverse communities,” he added. “Every story matters, and art gives us a voice in a world where we have too often been silenced.”

While it’s unclear what changes, if any, the Smithsonian will make to “The Shape of Power,” the institution has changed exhibits that have drawn controversy in the past.

The exhibit is currently on display through September 14. – Tristen Rouse/CNN

In 1978, religious groups sued over an evolution exhibition that they alleged violated the First Amendment, but a court sided with the Smithsonian, and the National Museum of Natural History kept the exhibit up.

But in 1995, the Smithsonian reduced the size and scope of an exhibit on Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, after veterans’ groups and lawmakers complained about what it said about World War II.

And in 2011, the National Portrait Gallery, which shares the same building as the American Art Museum, debuted “Hide/Seek,” the first major museum exhibition on gender and sexual identity at the Smithsonian.

The show featured the video “A Fire in My Belly” by the late artist David Wojnarowicz, which includes a scene where ants crawl over a crucifix, prompting uproar from the Catholic League and conservative members of the House of Representatives. It was quickly removed, but not without criticism from those that argued that the Smithsonian was capitulating to homophobic censorship.

The planned run for the “The Shape of Power” exhibition began November 8, 2024, and is to continue through September 14.

This story has been updated with additional information.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com