Residents of Somalia’s capital are casting ballots in local council elections, marking the first time in more than 50 years that voters will directly choose their representatives, a milestone overshadowed by opposition boycotts.

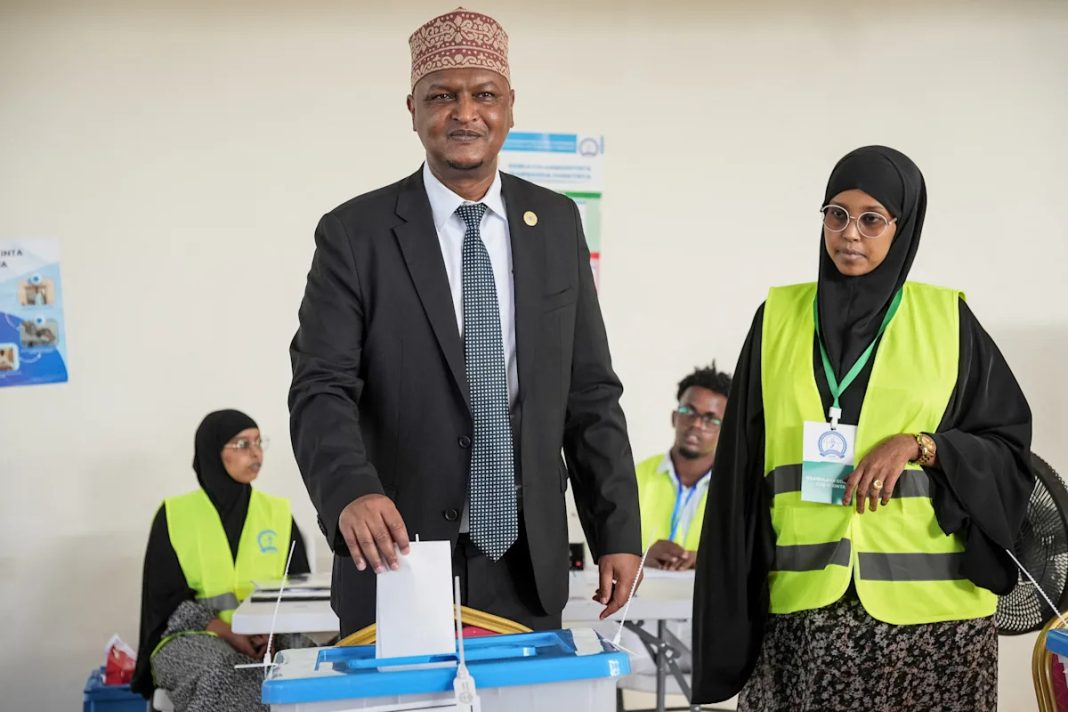

Polling stations across Mogadishu opened at 6am local time (03:00 GMT) on Thursday, with lines forming early as Somalis queued to participate in what President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has called a “new chapter in the country’s history”.

About half a million people registered to vote for 390 district council seats, with approximately 1,605 candidates competing across 523 polling stations in the capital.

Authorities deployed close to 10,000 police officers and imposed a city-wide lockdown, restricting vehicle and pedestrian movement, as well as stopping flights into the airport’s main city.

Security in Somalia’s capital has improved this year, but the government continues to battle the al-Qaeda-affiliated armed group al-Shabab, which carried out a major attack in October.

Information Minister Daud Aweis described the election as a “resurgence of democratic practices” after decades without them, while electoral commission chairman Abdikarim Ahmed Hassan assured voters they could trust security measures “100 percent”.

Somalia last held direct elections in 1969, months before an October military coup that kept civilians out of power for the next three decades.

After years of civil war following military leader Mohamed Siad Barre’s fall in 1991, the country adopted an unpopular indirect, clan-based electoral system in 2004, in which clan representatives select politicians, who in turn choose the president. The process has historically been deeply contested by candidates seeking top office.

The incumbent president, Mohamud, who won power twice through this system, announced in 2023 his commitment to transition to universal suffrage.

His government secured parliamentary approval for constitutional reforms and established a national electoral commission to oversee the transition, a move that has galvanised major opposition figures, including two former presidents.

An agreement reached in October 2024 between federal and regional leaders collapsed amid opposition resistance.

‘More of a symbolic vote’

Two former presidents have now openly criticised the Mogadishu vote. Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed described the procedures as “unfortunate,” attacking what he called an “exclusionary voter registration process” that lacks legitimacy. Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, known as Farmaajo, claimed the process “opens the door to dangers that threaten the security of the country”.

Two important federal member states, Puntland in the north and Jubbaland, bordering Kenya, have rejected the framework outright.

Major opposition figures, including the leaders of those federal states, met in the port city of Kismayo earlier this month, issuing a communique in which they threatened to hold their own separate national elections.

While signalling willingness to negotiate a “transparent, consensus-based electoral process”, they firmly rejected Thursday’s vote as premature and illegitimate.

Mahad Wasuge, the executive director of the Mogadishu-based Somali Public Agenda think tank, told Al Jazeera that the government had invested significant political capital in holding a direct election, which was relatively low-stakes because it was a local poll and offered an “easy win or easy exit”.

The government, he added, exercises significant control over Mogadishu’s political scene, so wouldn’t have faced a real threat.

But he noted “the vote isn’t supported by Somalia’s international partners and the major opposition figures have boycotted it, which is a red flag”. He characterised it as “more of a symbolic vote”.

The election comes as Somalia faces mounting security challenges in regions near the capital.

Al-Shabab, an armed group seeking the government’s overthrow, launched a major offensive in February 2025 that reversed government territorial gains.

The United Nations Security Council renewed the mandate of a UN-backed African Union peacekeeping mission this week, but it faces major funding shortfalls which could threaten its effectiveness and continuity.

The United States ambassador to the UN, Jeff Bartos, Somalia’s most important security partner, expressed deep concern over the deteriorating security situation, warning that Washington was no longer prepared to continue funding the mission.

The Trump administration has also recalled its ambassador to Mogadishu as part of a broader pullback of US diplomats from Africa, a move widely seen as signalling a downgrading of American interests in Somalia.