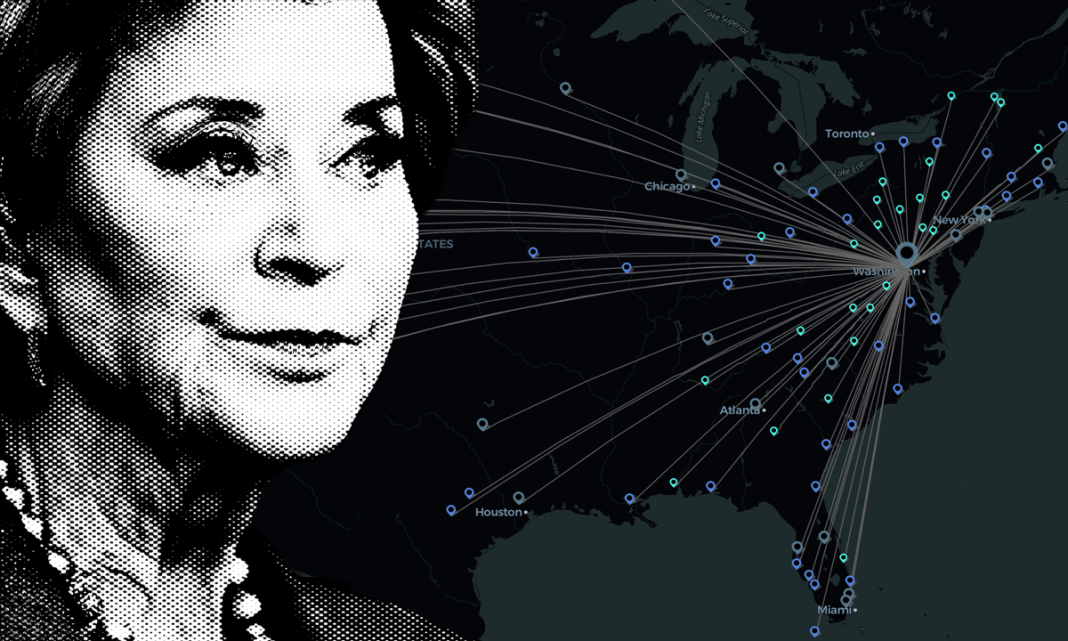

Cindy Marten spent four years as second in command at the U.S. Department of Education during the Biden administration before landing her current post as state chief in Delaware. But even for a veteran administrator, the past year has been a whirlwind of activity.

“The money’s coming. The money’s not coming. Oh no, we have to shut all of our Head Starts. No we don’t,” she said, describing the ping-ponging state leaders have been through between U.S. Secretary Linda McMahon’s efforts to downsize the department and court rulings reversing her actions. “We’re going through total D.C. chaos right now. Every time you turn right, it says turn left.”

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

To make sense of those shifts, she turns to Adam Schott, her associate secretary for student support and another top official at the Education Department during the Biden administration. In Washington, he oversaw the distribution of $122 billion in relief funds and was a primary point of contact on school improvement efforts. Having him on her team, Marten said, is like having “phone-a-friend on speed dial.”

Superintendent Cindy Marten’s team at the Delaware Department of Education includes several former staff members at the U.S. Department of Education. (Delaware Department of Education)

Schott is part of an exodus of former experts in federal policy, budgeting and data who have literally gone “back to the states,” to borrow McMahon’s catch-phrase. In her eyes, the state level is where the magic happens, away from the one-size-fits-all ethos of Washington. The irony is that a recent crop of state officials are themselves federal ex-pats who resigned or were displaced by McMahon’s layoffs. The 74 spoke to former department staff working in Maine, Maryland, Minnesota and Illinois. Because of the secretary’s efforts to shutter the department, there have never been so many federal staffers looking for work.

With the future of the federal government’s role in education uncertain, observers say their expertise is more valuable than ever.

“The people I worked with were there for like 15, 20 years,” said Kiara Nerenberg, a top data expert who resigned from her position with the National Center for Education Statistics just ahead of the mass layoffs in March. “There’s just so much knowledge that’s now looking for a place to land.”

Maryland’s ‘biggest score’

Marten’s team in Delaware also includes Denise Carter, who served as acting secretary at the department before McMahon was confirmed and has decades of experience in the federal government.

Marten called her “the right hand and the left hand” of multiple secretaries, including Democrat Arne Duncan and Republican Betsy DeVos. Carter stepped into the role of acting chief operating officer for Federal Student Aid last year following Richard Cordray’s resignation after a disastrous launch of the redesigned financial aid form. She oversaw corrections that contributed to a smooth rollout this year. Carter resigned in April and is now helping to overhaul Delaware’s outdated school funding formula.

Denise Carter

But Marten didn’t get all the talent. Because of its proximity to Washington, Maryland has scooped up several former staffers. Montgomery County even launched a hiring campaign targeting displaced federal employees.

Richard Kinkaid leads the division of college and career pathways at the Maryland State Department of Education. His “biggest score,” he said, was hiring Nerenberg, the former NCES staffer. One of her responsibilities was making “all of the tens and hundreds of thousands of points on maps that tell you where schools are,” she said. She was part of a project to identify neighborhood demographics — vital information for programs like Title I for low-income schools and grants for rural areas.

Now, she gathers data for career and technical education programs, but is also working to better align career-focused education with the needs of local labor markets. Having Nerenberg “catapulted us years ahead,” Kinkaid said.

Others searching for new jobs traveled far outside Washington.

Kiara Nerenberg

Tara Lawley spent 17 years with NCES, where she worked on both higher education and K-12 data collection. She was laid off along with over 1,300 other staff at the department in March while her husband, who worked in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, took the “fork in the road” option, a deferred resignation with several months of paid leave.

In August, she found her new position with the Illinois Board of Higher Education, where she’s the managing director of policy, research and fiscal analysis.

“We sold our house, tore our children out of everything they knew, and moved them across the country,” she said.

Her kids, 5 and 8, are doing fine, she said. But the experience reinforced her view that some decisions shouldn’t be left up to the states.

“How do you take a [special education plan] from one state to another? That’s a challenge that still exists and it’s certainly not going to be solved if you do it state by state,” she said. “If you’re in a state that’s really not doing well in K-12 education and you move to a different state, your kid can be really far behind.”

‘Connective tissue’

Some former staffers have branched out into agencies that focus on more than just education.

Sarah Mehrotra spent two years in the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, where she administered pandemic recovery efforts like curbing chronic absenteeism and preventing students from becoming homeless. She left the department in January along with other members of Cardona’s team, but knew she wanted to keep doing similar work.

Maryland Gov. Wes Moore’s Office for Children, includes former Biden administration officials like Carmel Martin, right. She served as a domestic policy adviser to Vice President Kamala Harris and as an assistant secretary in the Education Department during the Obama administration. (Office of Gov. Wes Moore)

Now she’s part of Maryland Gov. Wes Moore’s Office for Children, where she works on an initiative to address child poverty in specific communities. They include Frederick County’s Golden Mile, where more than 80% of students in two elementary schools qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, and Baltimore’s Cherry Hill neighborhood, where a state grant supports a math tutoring program.

When she was with the department, she said officials were “screaming from the rooftops” about ways districts could blend federal dollars with other sources of funding to re-engage students who became disconnected from school during the pandemic. Now, she said, “It’s super helpful to have the federal, state and local perspective” when working with grantees at the community level.

Those with federal experience, she said, can serve as “connective tissue” between states and the Education Department.

Republicans say there should be fewer ties to Washington, not more. At least one former department official, now at the state level, agrees. McKenzie Snow, Iowa’s education director, worked as an aide to DeVos and held top education positions in New Hampshire and Virginia.

Iowa Submits Plan to Combine Federal Education Funds, and Experts are Skeptical

She’s among those who, like McMahon, say that states are well equipped to manage federal education funds without the department’s strict oversight. Her state was the first to submit a request to roll federal funds into a block grant.

‘Their own innovation’

McMahon often points to reading gains in Mississippi and Louisiana to argue that the department is unnecessary.

“The states that are making great progress — it’s through their own innovation,” she said during a recent White House briefing. “It’s not coming from the Department of Education.”

But not all states have seen the same progress, and many have experienced significant turnover in leadership since the pandemic, which can contribute to disruption across an agency. Just this year, the state chiefs changed in Florida, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oklahoma and Utah, and since the beginning of 2023, more than 30 states have changed superintendents.

Having staff with some knowledge of federal grants and requirements is a plus right now, said Anna Edwards, co-founder and chief advocacy officer at Whiteboard Advisors, a consulting group.

“Given the uncertainty at the federal level, having those answers in house within a state is valuable,” she said. “During the shutdown, leaders couldn’t even talk to anyone at the department.”

As Teacher Evaluation Reforms Come Undone, 2 States React Very Differently to Using Test Scores to Rate Educators

Elizabeth Ross, who served in the department during the Obama administration, has worked for three chiefs since joining the D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education in 2020.

“It’s our job to make sure that students don’t feel that transition, that they continue to have access to all of the resources and support,” she said.

A former third grade teacher in D.C., she led federal efforts to turn around low-performing schools and revamp No Child Left Behind, with its tough testing and accountability requirements, into the more-flexible Every Student Succeeds Act.

Under Secretary Duncan, the department used stimulus funds as leverage to get states to adopt the Common Core standards and incorporate student test scores into teacher evaluations. The incentives often drew complaints about government overreach, but they also “catalyzed and generated a lot of reform,” she said.

Elizabeth Ross, now assistant superintendent of teaching and learning in the D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education, served at the Education Department during the Obama administration. (D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education)

What she didn’t have was frequent contact with teachers and parents directly affected by those programs. Now an assistant superintendent, she spends a lot of time in schools and often runs into teachers in the community who ask about specific curriculum materials.

She has new appreciation for their input.

“My perspective has shifted, compared to when I was at the federal level, on how important local buy-in is for the success of policies,” she said. “It’s something that I understand in a much, much deeper way.”